Most of us are guilty for scrolling through Instagram or TikTok and stumbling across a reel from wellness influencer and wondered whether their latest tip is worth trying. Perhaps it’s a fitness routine, a lemon balm drink which made the ‘weight fall off’, or advice about supplements or anxiety (Hasan F et al., 2023). Recent statistics show that 52% of Internet users in the European Union have searched for health-related information (Eurostat., 2018). In a world where influencers feel more like friends than strangers, it’s so easy to trust what they say. This “friend-like” feeling is called a parasocial relationship – a one sided sense of closeness that develops between followers and influencers (Bond BJ., 2016). When it comes to health advice, that closeness matters. A recent study by Kaňková et al. (2024) digs into this very issue: are influencers helping or hurting our health?

Doodle set social media concept influencer marketing elements 2025

Kaňková and Colleagues (2024)

Study Aim:

The researchers interviewed 12 health professionals who also create social media content (doctors, pharmacists, nutritionists, psychotherapists) to understand their perspectives on influencer-driven health advice. Their insights offer a fresh, nuanced look at the blurry line between helpful information and misleading content online.

Why Influencers Matter?

Social media has become one of the main places people go for health information. Influencers can have a genuinely positive effect – encouraging exercise, promoting vaccinations, and normalising conversations about mental health. Their relatable communication style builds trust and makes complex topics feel accessible. But the same qualities that make influencers persuasive also can make them risky. Many share health advice without professional qualifications. And because followers feel connected to them, that advice can strongly influence real health decisions. As one expert in the study said:

“Everyone who was overweight, then lost some weight and posted about it… is now a self-proclaimed expert on nutrition”

Kaňková et al., 2024

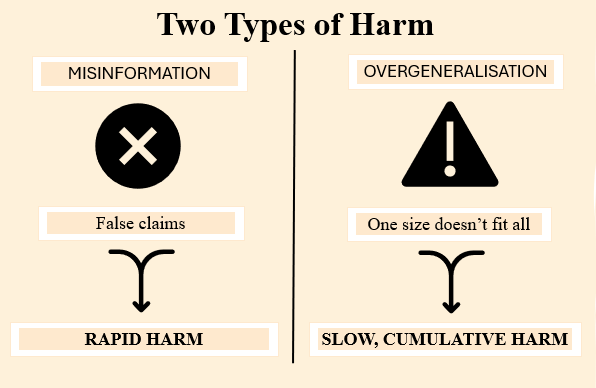

Misinformation vs. Overgeneralised Advice

We often assume the main danger online is misinformation – content that is factually wrong. But the study highlights an equally important problem overgeneralised health messaging. This refers to advice that is technically accurate for one person, but misleading when applied broadly. For example:

- “What I eat in a day” videos presented as templates for everyone

- Sharing a personal mental health journey in ways that cause followers to self diagnose

- Promoting exercise routines as universally safe or effective

One nutritionist explained that even “healthy” diets can be harmful if copied uncritically:

“If someone wants to inspire their followers to adopt an alternative diet, they should point out potential downsides”

Kaňková et al., 2024

Importantly, many experts said the consequences of misinformation and overgeneralised advice can be comparable – both can cause real harm, just on different timelines. Misinformation may cause immediate damage (Swire-Thompson B et al., 2020), while overgeneralisation can quietly disrupt health over months or years.

How Health Experts Feel About Influencers

The professionals interviewed held largely negative views of non-expert influencers offering health advice. Their main concerns included:

- Lack of expertise

- Personal experience does not equal knowledge

- Misplaced trust

- Self-diagnosis

- Oversimplification

Interestingly, the experts weren’t just critical – they also explained why they themselves post online. Their motivations included, educating people with accurate information, growing a client or patient base, creating supportive spaces for followers and counteracting misinformation including dispelling myths and correcting false claims.

One expert explained that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the spread of misinformation pushed them to start posting to “fight the myths” on their feed (Li W et al., 2023).

What can be improved?

Based on their experiences, the experts suggested several ways to elicit meaningful change in order to make social media a safer space for health content.

Better Public Health Literacy

People need tools to critically evaluate health posts – checking qualifications, understanding personal variability, and spotting red flags.

Education for Influencers

Many experts suggested training influencers to discuss health responsibly, including adding disclaimers.

Platform-level Regulation

Some called for stricter rules or content monitoring to limit misleading posts – highlighting inconsistencies like banned words but allowed dangerous trends.

Verification for Qualified Experts

A ‘badge’ for real professionals could balance out questionable content and reshape norms.

The paper is strong in conceptual framing, situating influencers within broader health communication debates, however, it falls short in empirical validation: without audience-focused data, claims about harm or benefit remain speculative. The reliance on expert influencers risks overemphasising credibility (Jenkins et al., 2020) while underplaying the reality that many popular influencers lack qualifications. Despite these limitations, the study is valuable as a cautionary lens, urging policymakers and health communicators to consider both risks and opportunities in influencer-driven health messaging. In summary, Kaňková and colleagues (2024) make an important contribution by highlighting the dual nature of influencer health communication – both empowering and potentially misleading. The paper is conceptually rich but would benefit from broader empirical grounding to strengthen its claims.

Conclusion

The study by Kaňková et al (2024) makes one message clear: the problem isn’t only misinformation – it’s also oversimplified advice that looks harmless but isn’t. Influencers can absolutely be forces for good, but only when their content acknowledges the complexity of real human health. As followers, we need to stay curious but sceptical; as content creators, influencers must prioritise responsibility over relatability; and as platforms, the goal should be transparency, verification and support for credible voices.

Ultimately, the healthiest thing we can do online is simple: think critically, ask questions, and remember that health advice is never truly “one size fits all”.

References

Eurostat (2018) https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20190124-1

Engel E, Gell S, Heiss R, Karsay K. Social media influencers and adolescents’ health: A scoping review of the research field. Soc Sci Med. 2024;340:116387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116387.

Bonnevie E, Smith SM, Kummeth C, Goldbarg J, Smyser J. Social media influencers can be used to deliver positive information about the flu vaccine: findings from a multi-year study. Health Educ Res. 2021;36:286–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyab018.

Durau J, Diehl S, Terlutter R. Motivate me to exercise with you: The effects of social media fitness influencers on users’ intentions to engage in physical activity and the role of user gender. Digit Health. 2022;8:20552076221102769. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221102769.

Li W, Ding H, Xu G, Yang J. The Impact of Fitness Influencers on a Social Media Platform on Exercise Intention during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Parasocial Relationships. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021113.

An S, Ha S. When influencers promote unhealthy products and behaviours: the role of ad disclosures in YouTube eating shows. Int J Advert. 2023;42:542–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2022.2148989.

Jenkins EL, Ilicic J, Molenaar A, Chin S, McCaffrey TA. Strategies to Improve Health Communication. Can Health Professionals Be Heroes? Nutrients. 2020;12:1861. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061861.

De Veirman M, Cauberghe V, Hudders L. Marketing through Instagram influencers: the impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int J Advert. 2017;36:798–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035.

Bond BJ. Following Your Friend: Social Media and the Strength of Adolescents’ Parasocial Relationships with Media Personae. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2016;19:656–60. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0355.

Swire-Thompson B, Lazer D. Public Health and Online Misinformation: Challenges and Recommendations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:433–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094127.

Hasan F, Foster MM, Cho H. Normalizing Anxiety on Social Media Increases Self-Diagnosis of Anxiety: The Mediating Effect of Identification (But Not Stigma). J Health Commun. 2023;28:563–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2023.2235563.